TB History

Dr. Mary Jane Logan McCallum gives a brief history of Indigenous tuberculosis in Manitoba

Colonialism, Racism, and the Creation of ‘Indian’ TB

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease contracted by inhalation. The bacterium can attack various parts of the body, but most commonly affects the neck glands and the lungs, causing fatigue, coughing and weight loss. Tuberculosis is a complicated disease that is very difficult to treat effectively and can recur under certain conditions. Currently, Manitoba has the second-highest rates of tuberculosis in Canada, after Nunavut.

From the late nineteenth century to the first half of the twentieth century tuberculosis became a major public health concern in Canada and elsewhere. First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples were disproportionately affected by serious and deadly cases of the disease compared to the general population. In the 1930s and 1940s and onwards, public health officials, doctors, and civil servants constructed ‘Indian TB’ as a separate and more virulent form of tuberculosis to which people of Indigenous ancestry were racially susceptible.

What these ‘experts’ chose to ignore was the impact of dislocation, poverty, malnutrition, overcrowding and inadequate housing on the health of First Nations, Inuit, and Métis. Colonialism in the forms of repressive economic, political, cultural, and social policies, military invasions, dispossession and white settlement, and the loss of resources from the land including the bison, all contributed to living conditions for Indigenous families that fostered the spread of the TB bacterium.

While rates of tuberculosis dropped dramatically in Canada after the 1960s, especially with the increasing use of antibiotics in the post-Second World War era, the disease has never been fully eradicated. Moreover, infection rates remain considerably higher within Indigenous populations than within the non-Indigenous Canadian population. For a recent government report on tuberculosis in Canada that addresses both historical and present dimensions of the disease, click here. For a general overview of tuberculosis published in the Canadian Encyclopedia Online, click here.

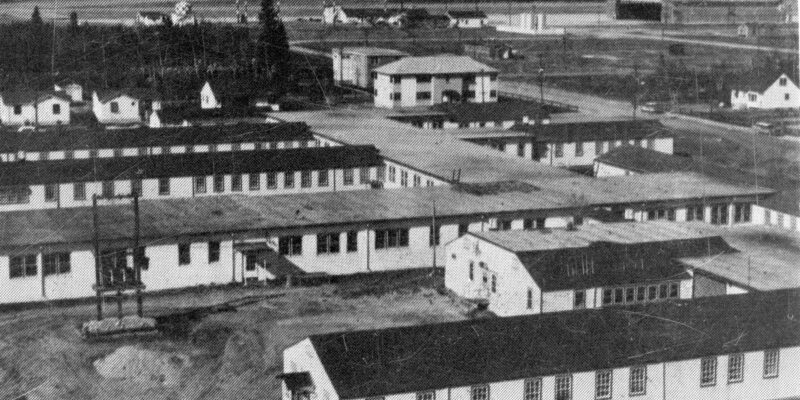

Sanatoriums and Indian Hospitals

In the 1930s medical professionals in Manitoba and across Canada increasingly warned of the “menace” posed by ‘Indian TB’ to the general population. In the 1940s, the federal Indian Health Service responded by opening two ‘Indian hospitals’ in the late 1930s (Dynevor Indian hospital and Fort Qu’Appelle Indian Hospital). The TB hospitals were part of a larger program to survey, institutionalize, and rehabilitate First Nations, Métis, and Inuit with TB. In Manitoba, the federal Indian Health Service arranged for the Sanatorium Board of Manitoba (San Board) to operate Dynevor Indian Hospital, Brandon Indian Sanatorium, and Clearwater Lake Indian Hospital. First Nations, Métis, and Inuit were also treated at the San Board’s provincially-funded flagship sanatorium at Ninette and at the St. Boniface Sanatorium run by the Grey Nuns in St. Vital (now part of Winnipeg).

Ideally, Indian hospitals and sanatoriums across Canada were to operate at half the cost of municipal and provincial hospitals. These care centers were under-funded and under-staffed, leading to sub-standard medical care. The infrastructure itself was generally inadequate; Indian hospitals were often opened in re-purposed federal or military buildings that were not suited to modern medical care. They were drafty in the winter, hot in the summer, damp, and infested with vermin. Despite these conditions and frequent poor treatment by staff, Manitoba newspapers in the 1930s and 1940s commonly reported the stellar work by the San Board and the federal government and assured the public that the “threat” of Indian TB was being managed.