St. Boniface Sanatorium

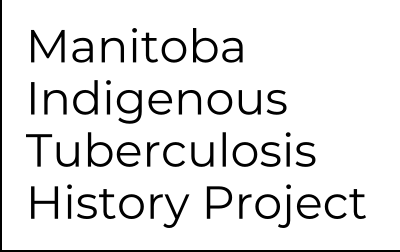

The St. Boniface Sanatorium officially opened in September 1931 on a 60 acre-plot of land in St. Vital, Manitoba, across the river from St. Boniface. The Grey Nuns of Montreal had been working in Manitoba since 1844. In the 1920s, they began building a case for a Catholic tuberculosis treatment centre as infections increased. The Ninette Sanatorium, operated by the Sanatorium Board of Manitoba, was located in a rural area on Pelican Lake and most patients had to travel great distances. After negotiations between Dr. Stewart, the superintendent of the Ninette Sanatorium, and the Grey Nuns, plans for the St. Boniface Sanatorium were forged. The first patient to be admitted in 1931 was an 8-year-old First Nations boy named Stanley Donald.

8-year-old Stanley Donald was the first patient admitted to the St. Boniface Sanatorium in 1931. He died at the Sanatorium in 1939. Grey Nuns of Montreal, L098-21-88.1

MITHP Senior Research Assistant Laura Bergen provides an overview of the treatment of Indigenous patients at the St. Boniface Sanatorium and some insights into her archival research at the Grey Nuns of Montreal Archive.

The sanatorium consisted of a four-storey main building which housed most of the patients, and contained an operating room, a laboratory, kitchens, a pharmacy, and a chapel. A power building stood beside the main building which had a large chimney and held the laundry and living quarters for the male staff. On the opposite side of the main building stood the preventorium (also known as the Annex). This building was originally two storeys and held the children’s quarters. A garage, a greenhouse, and a workshop also stood on the hospital grounds.

In 1937 the need to address the high rates of tuberculosis amongst the Indigenous population of Manitoba became urgent. The St. Boniface Sanatorium engaged in discussions about building a separate building on the site to house these patients; however, instead, a third floor was added onto the preventorium building to form a new ward. In June 1938 the hospital began admitting First Nations patients into this new ward, with a maximum of 35 patients recorded each year between 1938 and 1941. By 1942 the Dynevor Indian Hospital in Selkirk had become the primary treatment centre for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit patients in the area, and as a result the patient numbers decreased at the St. Boniface Sanatorium in the years following.

Child patients, most likely outside of the Annex. Un groupe de jeunes enfants, certains sur des lits ou des chaises roulantes, posent à l'extérieur du Sanatorium au grand soleil, Grey Nuns of Montreal, L098-22-25.8

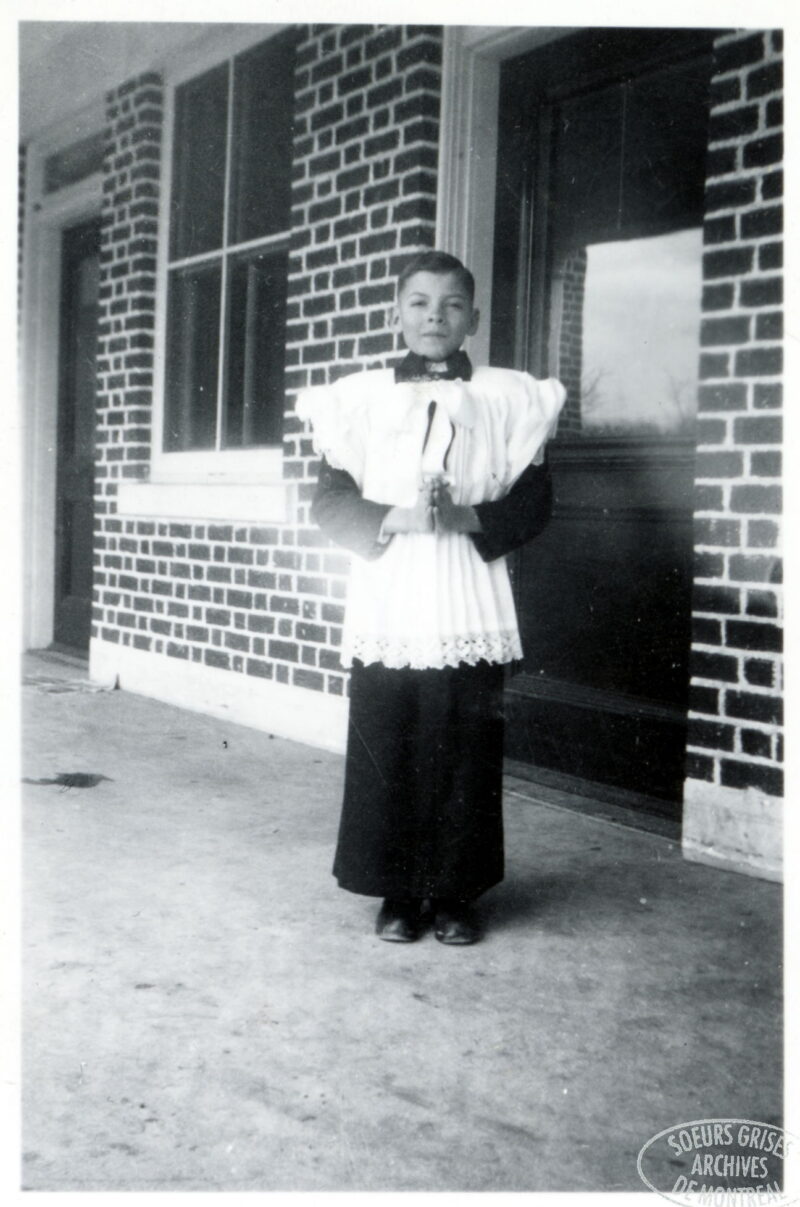

As a large institution, the hospital had the staff, space, and resources to undertake a wide range of surgical procedures. The most common procedure performed was the artificial pneumothorax, followed by thoracoplasties. Both were designed to collapse and “rest” the lung, by forcing air into the chest cavity or by removing ribs. Pneumothorax procedures were not permanent fixes, and many patients had to be “topped up” with air, resulting in thousands of procedures per year despite the hospital’s total patient capacity of just under 300.

Pneumothorax room, Une infirmière dans la salle de traitement pneumothorax. 1944, Grey Nuns of Montreal, L098-22-41

Religion was also a key component of life at the St. Boniface Sanatorium. Run by the Grey Nuns, the hospital was a Catholic institution with an ornate chapel that held Sunday masses. Former patients report being wheeled in their beds to the chapel to attend mass. The numbers of Catholic conversions and baptisms were recorded in annual reports, and there are stories of patients converting in their final hours of life in desperation. Christian holidays like Christmas and Easter were also celebrated with concerts and activities for children.

Patients who were not well enough to walk or sit in a wheelchair were wheeled to Mass in their beds. Messe des malades dans la chapelle du Sanatorium de Saint-Boniface. Grey Nuns of Montreal, L098-Y3C

By 1959 antibiotic drug therapies for TB reduced the need for hospital beds, and the hospital began accepting children with disabilities who required care. The hospital’s mandate shifted, and in 1962 the remaining TB patients were transferred to the Ninette Sanatorium. The main building and the power station still remain today as part of the St. Amant Centre.