When Can I Go Home? Patient Knowledge at TB Hospitals

July 5, 2022

Clearwater Lake Indian Hospital with airport in the distance, 1957, Mennonite Central Committee/Mennonite Archives of Ontario, CA MAO XIV-3.11.5-13

One of the legacies of Indigenous tuberculosis treatment in Manitoba is mistrust of the medical care system. Certainly, the lack of information that was shared by administrators, doctors, and Indian agents about the circumstances of loved ones' death and burial is the root of the circumstances that led the MITHP team to create the Missing Patients Initiative Research Guide. Lack of informed consent and treatment details, however, was common for patients in the hospitals as well as their families at home. This case study demonstrates that a lack of informed patient care informed patients' own perspectives on their time in hospital, and sometimes to deadly outcomes.

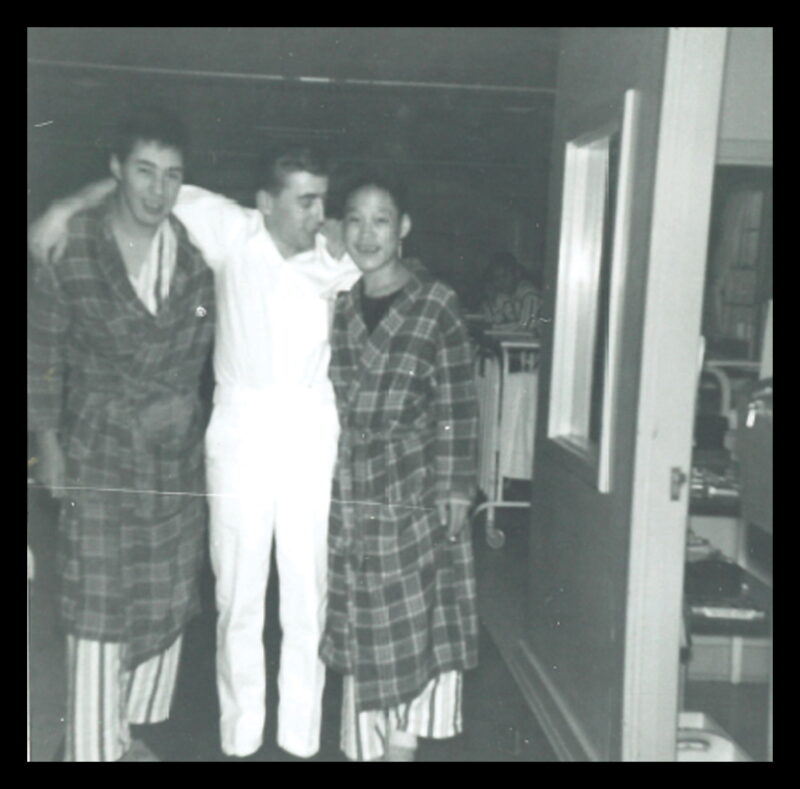

A male staff member with two patients, Clearwater Lake Indian Hospital, Willerton Collection, Manitoba Indigenous Tuberculosis History Project, WILL-01-24-001

In February of 1951, the Winnipeg Tribune reported that two young men, patients from the Clearwater Indian Hospital, died while running away from the institution. Sixteen-year-old Harold Stag and eighteen-year-old Thomas Highway disappeared on 24 January 1951. The boys’ frozen bodies were found by searchers a week later, about five miles from the institution, across the Hudson Bay Railway tracks and about 15 miles from The Pas. Searchers reported that the boys were “huddled together in sub-zero cold” and, according to the Tribune, neither of the boys were wearing the “customary moccasins. They were barefoot.”

Stag, from Moose Lake, and Highway, from The Pas, were local boys. No doubt they understood the dangers of heading out into the cold without adequate clothing or gear. A cutline in the Tribune article told readers that “authorities said the boys were almost ready for discharge [from the hospital],” a fact that might have made the young men’s decision to run away in the middle of winter without adequate clothing seem even more poorly thought out. But what the article did not mention was that Stag and Highway may not have had any idea that they were close to discharge.

Patient letters and Department of Indian Affairs correspondence reveal that it was not uncommon for Indian hospital and sanatorium patients to receive little information about how they were doing, or when they might expect to be discharged throughout their time in these institutions. As historian Maureen Lux notes in Separate Beds: A History of of Indian Hospitals in Canada, 1920s-1980s, medical and administrative staff at these facilities often prescribed treatments and moved patients between hospitals and sanatoriums without consultation and seldom with any explanation.

Inuit tuberculosis patient Anthony Amauyak from Chesterfield Inlet in Clearwater Sanitorium during Governor General's Northern Tour, March 1956, Library and Archives Canada, 3519999.

The tragedy of the deaths of Harold Stag and Thomas Highway, who perished in the cold Manitoba winter, was not only that they had inexplicably run away just as they were about to be released. The tragedy of their deaths was that practices at Indian hospitals and sanatoriums in Manitoba led to a persistent atmosphere of vulnerability and mistrust that excluded patients from decisions about their own care. Withholding this information from Stag and Highway almost certainly led to their efforts to take control of their health and situation in what they must have known was a desperate and dangerous escape.

For more on patient perspectives on their sanatorium experiences, read about the letters written by Inuit patients and watch the APTN Investigates episode "Writing Home."

Anne Lindsay, Postdoctoral Fellow

Erin Millions, Research Director